I’ve spent years covering how information flows — who controls it, how it shapes opinions, and why some stories spread while others vanish. Lately, I’ve been following a quieter revolution happening in classrooms: media literacy programs that teach teenagers not just to consume news, but to interrogate it. These programs don’t simply tell students what to think; they give them tools to ask better questions. And the change in how young people approach news can be startling.

Why media literacy matters now

Every time I explain a news event to readers, I’m aware of one thing: context is everything. Teenagers today live inside an attention economy where algorithms select their information diet. Platforms like TikTok, Instagram, and YouTube are brilliant at keeping attention, but they’re not optimized for truth. I’ve seen teenagers accept headlines or viral videos at face value because the content feels authentic or it confirms what their friends think.

Media literacy programs aim to shift that instinct. Rather than accepting content as passively consumed entertainment, students learn to examine source credibility, spot manipulation, and understand the incentives behind a piece of information — whether that comes from a news site, an influencer, or a meme.

What these programs actually teach

In classrooms I visited and in curriculum reviews I read, media literacy typically covers a few core competencies:

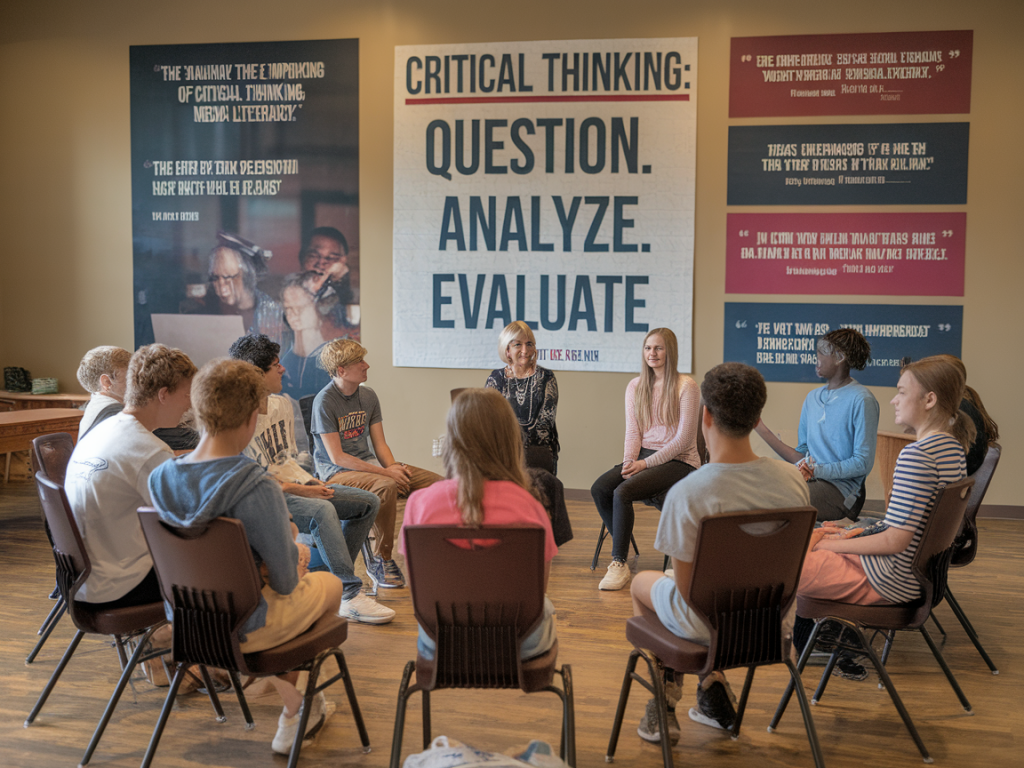

These are practical skills. I remember sitting in a classroom where students dismantled a viral claim by reverse-image searching a photo and finding its original caption from years earlier. The “aha” moment in that room was unmistakable: they realized their feeds could be deceptive by accident or design.

How teenagers change the way they consume news

When media literacy lessons are sustained — not a one-off assembly but a recurring part of the school year — I observe three clear shifts in behavior among teens.

These habits have ripple effects. Slower sharing reduces the velocity of misinformation; diversified sources make teenagers less susceptible to echo chambers; and critical discussions foster civic engagement because young people start asking what policies or stakeholders are implicated, not just who “won” a viral debate.

Programs and tools making a difference

Several organizations and platforms have put thoughtful curricula and tools into classrooms. I mention a few because they show different angles of the same effort:

When schools combine these external resources with local reporting — inviting journalists to class or taking students to a newsroom — the lessons land harder. Seeing how reporters verify facts and deal with deadlines demystifies the news ecosystem.

Classroom activities that work

I’ve watched several effective classroom routines that transform abstract skepticism into concrete skill:

Those activities do two things: they build muscle memory for verification techniques, and they create social norms where skepticism is rewarded rather than dismissed as cynicism.

Challenges and limits I’ve noticed

Media literacy isn’t a silver bullet. There are structural and cultural limits schools must acknowledge.

Even with these constraints, partial progress is valuable. A teen who learns to pause and check is less likely to amplify harmful content and more likely to seek out missing facts.

What schools, parents, and platforms can do now

If I could recommend three practical steps based on what I’ve seen work, they would be:

Platforms also have a role. Tools like context labels on articles, easy access to original sources, and clearer provenance for videos help. I’ve seen promising trials where a platform adds simple provenance tags and user willingness to click “see source” increases noticeably.

Resources I turn my students and readers to

| Resource | What it offers |

|---|---|

| News Literacy Project / Checkology | Interactive lessons and teacher resources for evaluating claims |

| Common Sense Media | Lesson plans on digital citizenship and news evaluation |

| First Draft | Verification techniques and case studies, often used by journalists |

| BBC Own It | Guidance blending online safety and media awareness for young teens |

These are starting points, not endpoints. The goal isn’t to create mini fact-checkers but to foster citizens who can navigate an information-rich world with curiosity and caution.

As I follow classrooms and track program outcomes, one thing keeps returning: media literacy changes the conversation. It nudges teenagers away from reflexive sharing and toward curiosity, away from spectacle and toward source. That shift doesn’t happen overnight, but when it does, you notice it in the way students argue, research, and engage with the world — and that matters.